Foraging in the Modern World : Foraging Bans

As foraging grows ever more popular some voices question its impact. In this series of articles, foraging teacher Mark Williams explores how it fits into a world that seems set on consuming itself…

Browse more blogs on the politics of foraging

Some public bodies have sought to ban foraging in certain areas, as if it were one activity.

It is not.

Bulldozing a forest, spraying glyphosphates on a hedgerow, or planting a monoculture of sitka spruce over hundreds of hectares might be described as individual activities. But foraging is as diverse as the many thousands of species that foragers seek. To conflate picking blackberries from a hedgerow with, say, gathering the eggs of a rare bird for dinner, is patently ridiculous. Brighton Council mooted such a ban in 2016, then rapidly backed down when it realised it would mean stopping kids gathering conkers or making daisy chains!

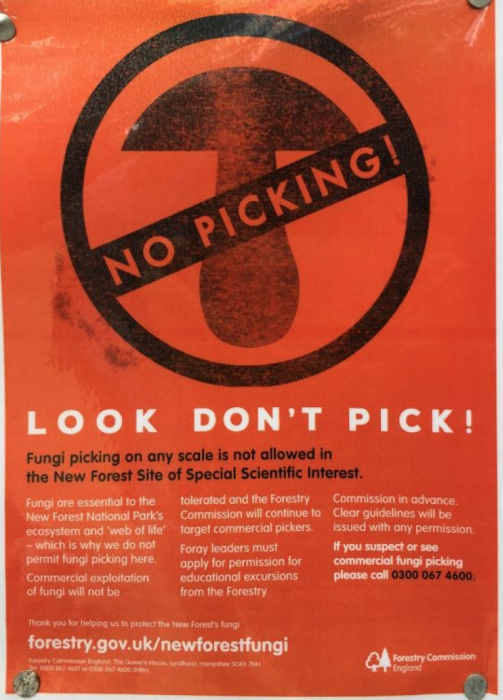

More focussed bans claiming worthy goals also look ill-advised and fall apart under scrutiny. In the following example I attempt to unpick the many pitfalls, straw dogs and own goals that befell Forestry England’s attempts to ban the picking of any fungi in the New Forest. This is a particularly gross example, but one that illustrates the sort of muddled, ill-advised ideas that some authorities have about foraging.

In 2016 the Forestry Commission England (since rebranded as Forestry England) attempted to impose a blanket ban on all fungi foraging in the New Forest. What they trumpeted as a “ban” turned out to have no basis whatsoever in law, so was unenforceable – a sham-bam. Commercial harvesting without permission was already illegal and FC rangers had enforced a “picking limit” for a number of years. While I have plenty to challenge these policies over they are not my focus here. The intention of the 2016 policy was clear – they wanted nobody to pick any fungi in the forest – and their campaign certainly put plenty of people off.

To get people onside with their “sham-ban” they circulated lots of scientific sounding “facts” about the impact of fungi foraging, which were widely regurgitated in the (mostly tabloid) press. Many of their claims sounded reasonable to the casual reader. But when challenged they produced no evidence to support their claims.

This is not surprising as all the scientific studies into the impact of picking mushrooms on future abundance clearly report zero impact, entirely refuting the Forestry Commission’s “facts”. Here are three pieces of research they should have read:

- “Mushroom picking does not impair future harvests – results of a long-term study in Switzerland”, SimonEgli et al, 2006

- “Effects of mushroom harvest technique on subsequent American matsutake production” – Daniel L. Luoma et al, 2006

- Norvel – “Loving the Chanterelle to Death: The Ten Year Oregon Chanterelle Project”. This research is now behind an academic paywall, but you can read its findings (and lots more interesting research on chanterelles) by going to Section 46. Recent Research in this document: “Ecology and Management of Commercially Harvested Chanterelle Mushrooms”.

Another unevidenced claim was that rare fungi were being picked. As discussed in this article, foragers are seldom interested in picking rare species – least of all rare fungi that are as hard to identify as they are to find. There are at least 2,700 species of fungi in the New Forest. Less than a dozen are routinely collected as food – none of them rare.

Devil’s Fingers, clathrus archeri, a rare fungus found in the New Forest. Of no culinary interest to foragers.

Another pillar of the ban was that foraging was a threat to fungal gnat populations, and the web of life that relies upon them. Again, this sounds plausible to the layperson, but doesn’t stand up to scrutiny if you understand edible fungi and foragers. The only species of fungi that are commercially traded in any quantity in the UK are chanterelles, winter chanterelles and hedgehog mushrooms (most of these are, ironically, gathered in vast Forestry Commission plantations in Scotland, a by-catch from sitka spruce monocultures).

It is no coincidence that all three of these species are both abundant and highly resistant to fungal gnat larvae. You can read my deep-dive into the ecology of these slow-growing, insect resistant fungi here. It is true that several gnat larvae attracting boletus species are also prized by mushroom foragers, but these are all so fast growing, susceptible to infestation, and quick to deteriorate that, despite the attentions of foragers, the vast majority of them rot in the woods by the thousands of tons each year – if they haven’t been kicked and trampled by a fungiphobe! Read more about the interactions between invertebrates and fast growing, fast rotting fungi here.

One cep worth eating, several more riddled with fungal gnat larvae and succumbing to bolete-eater fungus. I expect about only 1 in every 20 ceps I find to be in edible condition

Under pressure to justify the ban, the FC released their 2015 records of who was picking fungi in the New Forest. This was compiled from reports by FC rangers who had challenged people in the forest who appeared to be foraging for fungi. Its hard to imagine that these encounters were in any way cordial or educational, and the notion of “stop-and-search” going on in our woodlands is deeply worrying, especially as the records did not support their inference that hundreds of commercial pickers were stripping the forest. Their stop and search tactics exposed little more than some family groups enjoying connecting with nature and harvesting a little to take home, perhaps the odd individual with a couple of kilos, but absolutely nothing to support their claims.

There is absolutely nothing in their records to suggest any sort of commercial harvesting operations of the sort that the Forestry Commission likes to spread stories about. Besides, you can read my in-depth exploration of the notion of foraging for money in the UK here. (Spoiler: its not a lucrative occupation!)

More worrying than this gross exaggeration, there were also some clumsy redactions on the FC survey, which failed to obscure the fact that FC rangers were recording the ethnicity of foragers. When challenged on this the FC became very evasive and refused to discuss the situation further. Its no secret that in the UK a higher proportion of immigrants forage than do UK nationals – it is more closely engrained in their culture, and that is no bad thing. But tabloid newspapers love little more than an “Eastern Europeans are Pillaging our Forests” headline to whip up anti-immigrant sentiment. I explore this at length in this article. Why was the FC recording ethnicity? If it thought that perhaps Eastern European immigrants were taking more fungi than was reasonable, why didn’t it reach out to them with information signs in Polish or Romanian?

All this begs the question: why would the FC invent an unevidenced policy and try to present it as a legal ban? The Association of Foragers publicly called them out on these, and several other flawed arguments, while offering to work with them to make an evidence-based assessment of the condition of the New Forest mycota. After all, many of its members are accomplished mycologists who have been teaching about fungi in the New Forest (under licence from the Forestry Commission) for many years. You’d think they might have been the first people it would consult if it wanted to gain a meaningful understanding of what is going on with the mushroom? And wouldn’t research and education rather than a blanket ban, be a better way forward if there proved to actually be a problem?

In 2017 the FC abandoned its blanket ban on foraging fungi in the New Forest. But as I write, they still haven’t sought to engage in meaningful dialogue with the foraging teachers to whom they grant licences to run walks in the forest. They haven’t explained their recording of ethnicity, or their failure to engage with eastern European foragers. And they continue to promulgate misleading and unevidenced information about fungi in the New Forest.

Please note: These actions refer to the Forestry Commission England (now Forestry England) and specifically their behaviour with regard to the New Forest. Their are many excellent individuals in that organisation, trying to do good things, and it is not my intention to denigrate them, only this policy, and those that chose to pursue it contrary to all sensible advice and scientific evidence.

Putting this sorry tale aside, I’m pleased to say that foraging is increasingly being recognised as a powerful tool to restore connections between humans and the ecosystems of which they are part. Check out my events calendar where you will see events commissioned, promoted, subsidised and supported by organisations like The Woodland Trust, Scottish Natural Heritage, and yes, even Forestry Scotland!

1 Comment

I’m just getting into foraging I think it’s mad that local government are trying to stop this I know it’s only year ago this came out I’ve just seen it